A recent post on this blog mentioned the film, Beau Brummell: This Charming Man. One scene in the movie was particularly memorable. In it the prince regent, played by Hugh Bonneville, asked Beau Brummell (James Purefoy) how he tied his cravat. Instead of showing him, the Beau invited the prince to watch him dress. Mr. Brummell was known for his sartorial splendor and for his meticulousness in tying a rectangular linen cloth.

A recent post on this blog mentioned the film, Beau Brummell: This Charming Man. One scene in the movie was particularly memorable. In it the prince regent, played by Hugh Bonneville, asked Beau Brummell (James Purefoy) how he tied his cravat. Instead of showing him, the Beau invited the prince to watch him dress. Mr. Brummell was known for his sartorial splendor and for his meticulousness in tying a rectangular linen cloth.

The adoption of increasingly complex neckties by fashionable young men in the 1810s and 1820s swiftly attracted the attention of satirists and caricaturists. Brummell’s own legend revolved around a description of his morning dressing rituals, whereby his valet would present a gathered audience of friends and followers with Brummell’s failed knots on a silver platter – evidence of the master’s perfectionism in matters of the wardrobe. – The London Look

Brummel was the bane of his washerwoman and long-suffering valet, discarding a dozen snowy white, painstakingly ironed linens before he had achieved the perfect look. But he wasn’t the only “exquisite” who strove for perfection.

A German prince, visiting London at the turn of the century, noted: “an elegant then requires per week, twenty shirts, twenty-four pocket handkerchiefs, nine or ten pairs of ‘summer trousers,’ thirty neck handkerchiefs (unless he wears black ones), a dozen waistcoats, stockings à discretion.” – Poet of Cloth

During Beau Brummel’s reign as the premier dandy, no self respecting gentleman would wear less than three fresh cravats in a day. This was in an age when the household duty most dreaded by women was laundering and ironing clothes. Brummell was also known for his many innovations in tying the cravat. His biographer Captain Jesse wrote that Brummell’s collars were

“always fixed to his shirts and so large that before being folded down they completely hid the face and head; the neckcloth was almost a foot in height, the collar was fastened down to its proper size and Brummell standing before the glass, by the gradual declension of his lower jaw, creased the cravat to reasonable dimensions.” – Accessories of Dress, Katherine Morris Lester, Bess Viola Oerke, Helen Westermann, P 218.

This was easier said than done, for the fastidious Brummell was seldom satisfied with his creases in his first or second attempts. The Duke of Wellington, also a respected dandy, was known to wear only white cravats on the field of battle. Napoleon, who typically wore black stock, ironically chose to wear a white cravat for the first time during Waterloo in the Duke’s honor. From 1815 on the cravat was also known as a tie.

The Neckclothitania was published in September 1818 as a satirical document that poked fun at the most popular cravat styles of the time. Some of the cravats shown in the pamphlet were so elaborate and ridiculous that they clashed with Brummell’s idea that “style was essential in the quality of one’s linen rather than the extremity of it”. By 1818 colors were becoming fashionable, whereas in Brummell’s day only the purest white (blanc d’innoncence virginale) was acceptable.* The cloth for cravats was made of starched linen, though as some of the cravats styles evolved, a more relaxed, unstarched cloth was required for a looser, draped effect. By the 1830’s silk was used for neckcloths, as it still is used for today. In 1818, only a year after Brummell left for France, other cravat colors were introduced.

From Neckclothitania or Tietania, being an essay on Starchers, by One of the Cloth, published by J.J. Stockdale, Sept. 1st. 1818, engraved by George Cruikshank.

The following descriptions are directly from Neckclothitania:

The Oriental

The Oriental made with a very stiff and rigid cloth, so that there cannot be the least danger of its yielding or bending to the exertions and sudden twists of the head and neck. -Care should be taken that not a single indenture or crease should be visible in this tie; it must present a round, smooth, and even surface – the least deviation from this rule, will prevent its being so named. This neck-cloth ought not to be attempted, unless full confidence and reliance can be placed in its stiffness.-it must not be made with coloured neck-cloths, but of the most brilliant white. It is this particular tie which is alluded to in the following lines.

‘There, had ye marked their neck-cloth’s slivery glow,

Transcend the Cygnet’s towering crest of snow.’

The Mathematical

The Mathematical Tie (or Triangular Tie), is far less severe than the former. There are three creases in it. One coming down from under each ear, till it meets the kust or bow of the neckcloth, and a third in an horizontal direction, stretching from one of the side indentures to the other. The height, that is how far, or near the chin is left to the wearers pleasure. This tie does not occassion many accidents.The colour best suited to it, is called couleur de la cuisse d’une nymphe emue.’

Osbaldeston Tie

The Osbaldeston Tie differs greatly from most others. This neck-cloth is first laid on the back of the neck; the ends are then brought forward and tied in a large knot, the breadth of which must be at least four inches and two inches deep. This tie is well adapted for summer; because instead of going round the neck twice, it confines itself to once. The best colours are ethereal azure.

Napoleon Tie

Why this particular Tie was called Napoleon, I have not yet been able to learn, nor can I even guess, never having heard that the French Emperor was famous for making a tie – I have, indeed, heard it said, that he wore one of this sort on his return from Elba and on board the Northumberland, but how far this information is correct, I do not know. It is first laid as in the former, on the back of the neck, the ends being fastened to the braces, or carried under the arms and tied on the back. It has a very pretty appearance, giving the wearer a languishingly amourous look. The violet colour, and la couleur des levres d’amour are the best suited for it.

American Tie

The American Tie differs little from the Mathematical except that the collateral indentures do not extend so near to the ear, and that there is no horizontal or middle crease in it. The best colour is ocean green.

Mail Coach Tie

The Mail Coach or Waterfall, is made by tying it with a single knot, and then bringing one of the ends over, so as completely to hide the knot, and spreading it out, and turning it down in the waistcoat. The neck-cloth ought to be very large to make this Tie properly – It is worn by all stage-coachmen, guards, the swells of the fancy, and ruffians. To be quite the thing, there should be no starch, or at least very little in it – A Kushmeer shawl is the best, I may even say, the only thing with which it can be made. The Mailcoach was best made out of a cashmere shawl and had one end brought over the knot, spread out and tucked into the waist. This style was particularly popular with members of the ‘Four-in-Hand Club’.

The Trone d’Amour

The The trone d’Amour is the most austere after the Oriental Tie – It must be extremely well stiffened with starch. It is formed by one single horizontal dent in the middle. Colour, Yeux de fille en extase.

Irish Tie

This one resembles in some degree the Mathematical, with, however, this difference, that the horizontal indentture is placed below the point of junction formed by the collateral creases, instead of being above. The colour is Cerulean Blue

The Ballroom Tie

The Ballroom Tie when well put on is quite delicious – It unites the qualities of the Mathematical and Irish, having two collateral dents and two horizontal ones, the one above as in the former, the other below as in the latter. It has no knot but is fastened as the Napoleon. This should never of course be made with colours but with the purest and most brilliant blanc d’innocence virginale .

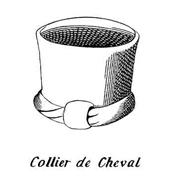

Horse Collar Tie

Horse Collar Tie

The Horse Collar has become, from some unaccountable reason, very universal. I can only attribute it to the inability of its wearers to make any other. It is certainly the worst and most vulgar, and I should not have given it a place in these pages were it not for the purpose of cautioning my readers, from ever wearing it – It has the appearance of a great half-moon, or horse collar – I sincerely hope it will soon be dropped entirely – nam super omnes vitandum est.

Hunting Tie

The Hunting or Diana Tie, (not that I suppose Diana ever did wear a Tie) is formed by two collateral dents on each side, and meeting in the middle, without any horizontal ones – it is generally accompanied by a crossing of the ends, as in the Ball Room and Napoleon. Its colour Isabella – This cloth is worn sometimes with a Gordian Knot.

Maharatta Tie

The Maharatta or Nabog Tie, is very cool, as it is always made with fine muslin neck-cloths. It is placed on the back of the neck, the ends are then brought forward, and joined as a chain link, the remainder is then turned back, and fastened behind. Its colour, Eau d’Ispahan.

By 1828 Beau Brummell had lived in France for 9 years, a disgraced exile. But his influence in men’s fashion lived on.

His collar was copied and grew to extreme heights that covered the ears and were held away from the neck by whale bone stiffeners, and meant men could no longer turn their heads to see, but had to turn their entire bodies. It did however spawn an industry of publications and experts who taught men of fashion how to tie their cravats. – The Regency Neckcloth

The book The Art of Tying the Cravat (demonstrated in sixteen lessons as shown in the illustration below) was originally published in 1828 by H. Le Blanc Esq.

Plate B, The Art of Tying the Cravat

The fronticepiece of Mr. Le Blanc’s book shows an engraving of the author wearing an elaborate white cravat, the acme of full dress London fashion in 1828. In that year there were 32 types of cravats. Those made of black silk or satin were for general wear, while white cravats with spots or squares were considered half dress. The plain white cravat was admitted at balls or soirees where colored cravats were prohibited.

The art of tying the cravat demonstrated in sixteen lessons, including thirty-two different styles, By H. Le Blanc.

The following description comes from The Art of Tying the Cravat:

THE Cravate Americaine is extremely pretty and easily formed, provided the handkerchief is well starched. When it is correctly formed it presents the appearance of a column destined to support a Corinthian capital. This style has many admirers here, and also among our friends the fashionables of the New World, who pride themselves on its name which they call Independence; this title may to a certain point be disputed, as the neck is fixed in a kind of vice which entirely prohibits any very free movements – The Art of Tying the Cravat

Read more about this topic at these links:

- The Beaux of the Regency, Lewis Saul Benjamin, 1908

- The Cut of Men’s Clothes, 1600-1900, PDF Document