A Dance with Jane Austen: How a Novelist and her Characters went to the Ball, Susannah Fullterton

A Dance with Jane Austen: How a Novelist and her Characters went to the Ball, Susannah Fullterton

“Ah”, I said, when I saw Susannah Fullerton’s book in my mail box. “Here’s just the book I need.” Some of the biggest gaps in my Austen reference library concern dance and music. Whenever I wanted to find out more about the social customs of balls and dancing, how ladies and gentleman conducted themselves, the food served at supper balls, the etiquette of a gentleman’s introduction to a lady before he could dance with her, precisely when the waltz became acceptable not only among the racy upper crust but with villagers in the hinterlands as well, and the difference between private balls and public balls, I had to consult a variety of books. This was time-consuming, and a bit frustrating, for there were variations in details that each source offered.

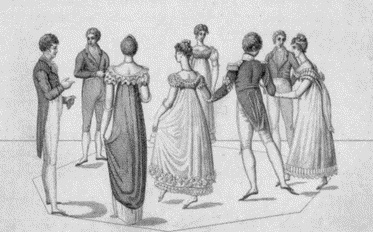

And now Susannah Fullerton has come to my rescue! Readers who have visited the Jane Austen Society of Australia (an excellent site) know that Ms. Fullerton is its president, and that she has written a previous book, Jane Austen and Crime. A Dance With Jane Austen is a compact illustrated book crammed with information, but written in a relaxed and accessible style. Topics include: Learning to dance, Dressing for the dance, Getting to and from a ball, Assembly balls, Private balls, Etiquette of the ballroom, Men in the ballroom, Dancing and music, ‘They sat down to supper’, Conversation and courtship, The shade of a departed ball, and Dance in Jane Austen films.

Ms. Fullerton culls information from Austen’s letters, novels, and historic texts, such as The Complete System of English Country Dancing, by Mr. Wilson, a dancing master of some renown and decided opinions. She also describes how Beau Nash, the influential master of ceremonies and taste maker in Bath, laid down a set of rules for Society to follow. Nash single-handedly changed a small, sleepy city into THE playground for the smart set with his dictums and innovations, which lasted well beyond his death.

Jane Austen was no stranger to Bath’s public assemblies, or to dancing in private settings. She loved to dance and rarely said no when a man approached her for a set. Jane danced as often as she could, wryly observing to her sister when she was in her thirties and when partners became scarcer: “You will not expect to hear that I was asked to dance, but I was.”

Getting to a ball might be problematic for those who had no means to keep horses or carriages. It made little sense to walk miles in fancy garb over dirt roads to a social event, and so arrangements needed to be made for those who were going to a dance to piggy-back with individuals who were willing to take them. This meant arriving and leaving a dance on someone else’s schedule. Catherine Morland did not walk to the Assembly Rooms, but took a sedan chair, for private carriages were seldom used within Bath proper. Her journey from “Great Pulteney Street to the Upper Rooms would have cost her between one shilling and six pence and two shillings (one way) – an expensive luxury at the time.”

The dancing ritual was one of courtship, and Jane Austen took full advantage of a ball to set the stage for character development. In each novel she takes a different approach. Lizzie and Darcy tense relationship began at the Meryton Assembly Ball, a situation that was not helped at the private ball at the Lucas’s house nor at the Netherfield Ball, where Lizzie’s family behaved abominably. The dances in Mansfield Park serve to show how selfish the characters are, and to point out Fanny’s isolation from the neighbors. Dancing masters taught children to dance properly, and they received further practice at children’s balls, but Fanny had few opportunities for practice, and she felt tense when she was prominently displayed at her birthday ball. Jane Austen masterfully used the dances in Emma to show how Emma never quite loses sight of Mr. Knightley even as she dances with Frank Churchill, and one gets a good sense of the frustration Catherine Morland feels at not being able to dance at her very first ball in Bath, for there was no one to introduce her and Mrs. Allen properly, or the utter irritation she feels when John Thorpe ruins her well-laid plans to dance with Mr. Tilney at a later assembly ball. Austen also uses balls to demonstrate how outrageous Marianne Dashwood’s behavior is towards Willoughby, breaking many rules of etiquette and decorum.

Ms. Fullerton sets aside a few pages to discuss dances in films. These elaborately staged scenes are highly popular with film buffs. The costumes are beautiful, as is the music, and the settings are often quite lavish. But be aware that most of the dances and music are often inaccurate and chosen for cinematic effect. (As an aside, I was glad to note that Susannah’s take on Pride and Prejudice 1940 was similar to mine.)

Insights such as these make this book a sheer pleasure to read. A Dance with Jane Austen will be a valuable addition on the book shelves of any Regency author, Janeite, and history buff. As Susannah Fullterton says about her book:

Dances in the Regency era were almost the only opportunity young men and women had to be on their own without a chaperone right next to them, and dancing provided the exciting chance of physical touch. ..Dances were long – one often spent 30 minutes with the same partner – so there was plenty of opportunity for flirtation, amorous glances, and pressing of hands. After the dance was over, there was all the pleasure of gossip about everything that had happened.”

A Dance with Jane Austen will be available in October. Readers who are lucky enough to go to the Jane Austen Society Annual General Meeting in New York in a few weeks will have the opportunity to meet Ms. Fullerton! I give this book 5 out of 5 Regency tea cups.

Preorder the book at this Amazon.com link or at Frances Lincoln Publishers

Hardcover: 144 pages

Publisher: Frances Lincoln (October 16, 2012)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0711232458

ISBN-13: 978-0711232457

Please note: The blue links are mine; other links are supplied by WordPress. I do not make money from my blog. I do, however, receive books from publishers to review.

Rolinda Sharples’s 1817 painting of the Cloak-Room, Clifton Assembly Rooms is a familiar one to most Jane Austen fans. This image graces many book covers and has been used for depicting life in the Regency era. Looking closely, one sees that the assembled party seem to be enjoying the occasion as they wait and chat. A lady’s maid is helping a woman exchange her shoes, a man holds a lady’s fan, and the ladies are wearing an assortment of pale dresses, and colorful headwear and shawls. John Harvey, author of

Rolinda Sharples’s 1817 painting of the Cloak-Room, Clifton Assembly Rooms is a familiar one to most Jane Austen fans. This image graces many book covers and has been used for depicting life in the Regency era. Looking closely, one sees that the assembled party seem to be enjoying the occasion as they wait and chat. A lady’s maid is helping a woman exchange her shoes, a man holds a lady’s fan, and the ladies are wearing an assortment of pale dresses, and colorful headwear and shawls. John Harvey, author of