Vauxhall Gardens opened in 1661. The most famous of London’s diarist’s, Samuel Pepys, recorded in his diary that he visited Vauxhall Gardens no less than twenty four times. The first time he recorded a visit to the gardens was on 29th March 1662, when Vauxhall it really was just a country inn set within a pleasant garden setting with walks and flower beds. It was approached from a path from the Thames and the Vauxhall stairs. Visitors would cross the Thames in a boat from the north bank. They generally would bring their own picnics.

Map of Vauxhall Gardens in 1800. Click on image to enlarge. Image @Ideal Homes: History of South East Suburbs (see link below).

Amateur musicians would perform in the gardens and sometimes the visitors themselves would provide their own entertainment. This was the first time that ordinary people could enjoy gardens like this, which was a unique social aspect at the time of Pepys. It was a freeing of social codes. Such gardens were usually found in the country estates of the nobility.

People from different levels of society could meet freely and strangers could meet within the gardens. In the usual course of their lives there were strong social codes about friendships and who could talk to whom. The gardens were a place to be free of many social constraints, where males and females could meet. It was also an ideal place for the business of prostitutes.

Interior view of the elegant music room at Vauxhall Gardens. Engraving by H. Roberts, 1752. Image @1st Gallery.com

Over the centuries various owners and managers oversaw Vauxhall gardens . The greatest of these was Jonathan Tyers. He came from a family of fellmongers from Bermondsey in the east End. Fellmongers were dealers in leather hides.

Tyers was a shrewd businessman and understood how to advertise and popularise the gardens. He was also good at reinventing himself as a gentleman, landowner, wit, urbane host, and patron of the arts. He owned the gardens from 1729 to his death in 1767 and saw Vauxhall gardens at the height of its fame and popularity. His most important guest was The Prince of Wales, who had his own booth within the gardens.

All of society, from the aristocracy, to landowners, to the ordinary working people came to Vauxhall. For special events Tyeres would raise the price to attract only certain people but generally the price was one shilling and this price remained the same for sixty years. He offered season tickets for a guinea.

The season ticket comprised a metal tag embossed on one side with a scene of classical mythology and the other side was printed with the ticket holders name. There is quite a selection of these season tickets in various collections.

In 1740 a Vauxhall evening would begin at 7pm.The visitors would get into a boat from Westminster and alight at the Vauxhall Stairs on the south bank, very close to where Lambeth Palace, the home of the Archbishop of Canterbury, was located. Visitors would walk through the main entrance which fronted the River Thames and proceed along The Grove with the supper boxes lining the walkway on either side.

In front of the boxes stood the orchestra building.

A statue of the composer Handel could be seen in front of this. The gardens were famous at this time for giving performances of new pieces composed by Handel or other composers well known at the time, such as Arne and Boyce.

Visitors would have the chance to see wealthy people promenading through the gardens wearing the latest expensive fashions.

The fifty large supper boxes were able to entertain up to ten people to supper. Each box was decorated with an original painting. Surprisingly fourteen of these paintings still survive.

The Grand Walk led to the golden statue of Aurora or the Rural Downs where there was a life size statue of Milton. This reminds me of the 18th century gardens at Painshill in Surrey which have been restored very much to their former glories. At Painshill there are grand vistas, a Turkish tent, mysterious grottos near the lake, a ruined Abbey, a hermits lodging and a Roman temple as well as many large statues from Greek mythology set within groves.

The Vauxhall experience therefore is still possible to experience. If Vauxhall was intended, as the gardens at Painshill were, then each setting was meant to create a different mood or spiritual experience. There is no record of Jane Austen visiting Vauxhall but she obviously knew about it. She stayed with her brother Henry at Hans Place which is almost directly across the Thames from Vauxhall.

It is about half a mile from the river bank but the lights, the sounds of the music and fire works exploding would easily have been noticed from miles around. In Mansfield Park the walk in the park at Sotherton owned by Mr Rushworth have echoes of Painshill and Vauxhall.

The Vauxhall Supper began about 9pm as dusk fell. It comprised of Vauxhall ham, cold meats, salad, cheeses custards, tarts, cheesecakes and other puddings. As night fell during the supper a whistle was blown. Servants lit thousands of lamps positioned strategically about the gardens and illuminated the scene. The effect was sensational.

The installation at The Museum of London recreated how the costumes in Vauxhall would look at night. Hats in this exhibit by contemporary milliner Philip Treacy.

By the mid 18th century semi circular piazzas had been opened in the north and south ranges of boxes. Behind the north range of boxes Tyeres had the Rotunda built. This was a covered concert room for wet weather.

Female costume. Note how the yellow light (from oil globes or candles) affected the colors of the costumes. Some colors would not show up well. People kept this effect in mind when choosing evening wear. Image @Tony Grant

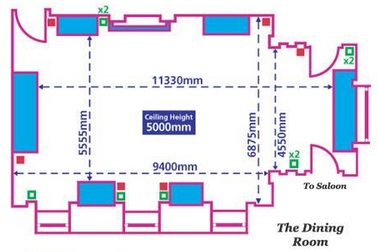

Later a Pillared Saloon was added to the eastern side of the Rotunda. Within the Rotunda, Tyers got Francis Hayman to paint four huge canvases showing Britain’s victories in the Seven Years War. Each canvas was 12 feet by 15 feet. Only two oil sketches remain of the originals and an engraving is still in existence. The paintings have disappeared. Jonathan Tyers and Francis Hayman gave British art in the 1760’s its direction.

Vauxhall was also famous for its music. Many famous songs, some still known and sung today, were commissioned for the gardens. The most famous of which is, Lass of Richmond Hill. The singers became the superstars of their day, Thomas Lowe, Cecilia Arne, Joseph Vernon and Charles Dignum.

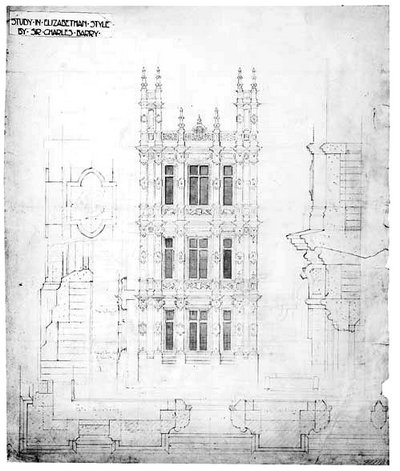

In 1758 the orchestra building was replaced by a neo gothic structure. The famous architect, Robert Adam, wrote to his brother:

“ I am now scheming another thing, which is a temple of Venus for Vauxhall which Mr Tyers proposes to lay £5000 upon……”

David Coke, author of a recent book on Vauxhall Gardens, wrote that this building was probably never built. Jonathen Tyers died in1767 and his children took over who themselves were followed by their children until 1822.

The gardens closed finally closed on 25th July 1859. By this time Vauxhall had become run down and dilapidated. Its popularity had waned. Vauxhall railway station is situated opposite to where the entrance to Vauxhall gardens was. It epitomises the changes that were occurring in the world and society. People were able to travel about the country easily. The ordinary people preferred to go to the seaside and the new entertainments that were provided at these holiday resorts. If you go to Brighton on the south coast in Sussex you can experience the delights of Brighton Pier.

It is a Victorian construction and many of the buildings on it date back to Victorian times. The pier has more than an echo of the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. These Victorian piers built at popular resorts have been described as Vauxhall piers.

Recently I was looking at an old map showing the layout and design of Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. I could see Kennington Road marked clearly on the map bordering the southern border of where the pleasure gardens had been. It showed the road curving slightly. It struck me that I know that part of Kennington Road well. Vauxhall is part of the London Borough of Lambeth. My wife Marilyn worked for over ten years in schools in Lambeth and often got off the train at Vauxhall and walked to her inner city school in Walnut Tree Walk next to the Lambeth Walk that is of Charley Chaplin and that song, fame. We decided that we would go for a walk around Vauxhall and see if we could find any signs or remains of the pleasure gardens.

Marilyn, myself and Abigail, our youngest daughter, got off the train at Vauxhall and walked across the road to a pub which has its windows blacked out. This pub is now famous for the performance of strippers. This must be reminiscent of the courtesans who sold their bodies in the pleasure gardens of the 18th century perhaps.

Behind the pub is a small park called Spring Park. This area was covered in Victorian terraced housing up to the second World War and then during the Blitz on London many were destroyed. After the war, to commemorate the old pleasure gardens, Lambeth Council decided to make the area into a park again. This was the site of the original pleasure gardens. We had found it. To one side you can see the green glass and concrete structure that is MI6.The entrance to the park announces that this is Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, although it is officially called Spring Gardens. When I researched the old gardens I discovered that indeed it used to called Vauxhall Spring Gardens when it first began. There is a large sign board as you walk into Spring Gardens which provides a display of old pictures of the gardens and a history of the site.

To the north of the park is Tyers Road commemorating Jonathen Tyers. There is a city farm called Vauxhall City farm on the site where the battle of Waterloo was re-enacted. In the far right eastern corner there is situated St Peter’s Church, which is reputedly on the very site of the Neptune Fountain that was placed at the end of The Grand Walk.

St. Peter's Church, Kennington Lane, on the site of the Neptune Fountain at the end of the Grand Walk. Image@Tony Grant

There are no remains of the actual pleasure gardens to be seen in the new park. Because it is an open area with walkways and grassy mounds within the park you can get a sense of the size and feel of the original pleasure gardens.

Here are some quotations from people who visited the gardens at different times during its existence.

An article in The Spectator 1712:

We were now arrived at Spring-Garden, which is exquisitely pleasant at this time of the Year. When I considered the Fragrancy of the Walks and Bowers, with the Choirs of Birds that sung upon the Trees, and the loose Tribe of People that walked under their Shades, I could not but look upon the Place as a kind of Mahometan Paradise. Sir Roger told me it put him in mind of a little Coppice by his House in the Country, which his Chaplain used to call an Aviary of Nightingales.

A letter to a Lord describing the Spring gardens in 1751:

These Gardens, containing about twenty Acres and a Half, make part of a Mannor, belonging to His Royal Highness the PRINCE OF WALES, as Earl of Kennington; the famous black Prince, son to our immortal Edward III, having anciently had a Palace there. —But leaving Antiquity, I shall proceed to the present State of the Spot, which is the Subject of your Lordship’s obliging Command; after observing, that the Hint of this rational and elegant Entertainment, was given by a Gentleman, whose Paintings exhibit the most useful Lessons of Morality, blended with the happiest Strokes of Humour.

Being advanc’d up the Avenue, by which we enter into the Spring-Gardens; the first Scene that catches the Eye, is a grand Visto or Alley about 900 Feet long, formed by exceedingly lofty Sycamore, Elm, and other Trees. At the Extremity of this Visto, stands a gilded Statue of Aurora, with a Ha ha; over which is a View into the adjacent Meads; where Haycocks, and Haymakers sporting, during the mowing Season, add a Beauty to the Landskip. This Alley (a noble Gravel Walk throughout) is intersected, at right Angles, by two others. One of these Alleys (at the Extremity whereof, to the Left, a [p.3] fine Picture of Ruins is seen) extends about 600 Feet; being the whole Breadth of the Garden, or Spring-Gardens, as they are commonly called, which Terms I shall use indiscriminately.

These are the thoughts of a German Prince in 1827:

Yesterday evening I went for the first time to Vauxhall, a public garden in the style of Tivoli at Paris, but on a far grander and more brilliant scale. The illumination with thousands of lamps of the most dazzling[157] colours is uncommonly splendid. Especially beautiful were large bouquets of flowers hung in the trees, formed of red, blue, yellow, and violet lamps, and the leaves and stalks of green; there were also chandeliers of a gay Turkish sort of pattern of various hues, and a temple for the music, surmounted with the royal arms and crest. Several triumphal arches were not of wood, but of cast-iron, of light transparent patterns, infinitely more elegant, and quite as rich as the former. Beyond this the gardens extended with all their variety and their exhibitions, the most remarkable of which was the battle of Waterloo.

Here is part of a satirical poem written for the PUNCH magazine in 1859 and depicts the decline of the gardens before they were finally closed:

Comrades, you may leave me sitting in the mouldy arbour here,

With the chicken-bones before me and the empty punch-bowl near.

‘Rack’ they called the punch that in it fiercely fumed, and freely flowed:

By the pains that rack my temples, sure the name was well bestowed.

Leave me comrades, to my musings, ‘mid the mildewed timber-damps,

While from sooty branches round me splutter out the stinking lamps.

While through rent and rotten canvas sighs the bone-mill laden breeze;

And the drip-damp statues glimmer through the gaunt and ghastly trees.

And the ode goes on and on. It has become a depressing place.

Written by Tony Grant, London Calling

More on the topic:

- David Coke’s excellent site: Vauxhall Gardens

- Vauxhall Gardens

- Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens

- Friends of Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens

- Pleasure Gardens Part 2

- Vauxhall Gardens 3

- Galleries of Modern London at the Museum of London

- Fireworks and the Very Useful Application of Bishops

- Effra

- History of South East Suburbs

- Discovering the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens

- William Hogarth’s Gold Admission Ticket to Vauxhall Gardens

- Ranelagh and Vauxhall Gardens

- Will They Chop Down the Mulberry Trees?

- English Pleasures of Vauxhall

- Vauxhall Gardens: A History, a Review