She lost her pattens in the muck

& Roger in his mind

Considered her misfortune luck

To show her he was kind

He over hitops fetched it out

& cleaned it for her foot…

From the Middle Period Poems of John Clare (1820s)

It is commonly acknowledged that country roads in the day of Jane Austen became muddy and rutted in heavy rains, and therefore nearly impassable. In cities and towns, streets required constant sweeping of horse dung and dirt by street sweepers. Ladies wearing long white gowns and soft satin or kid slippers were constantly dodging dirt, protecting their hems from wet grass, and finding ways to walk on roads and cobblestones whose condition were poor at best.

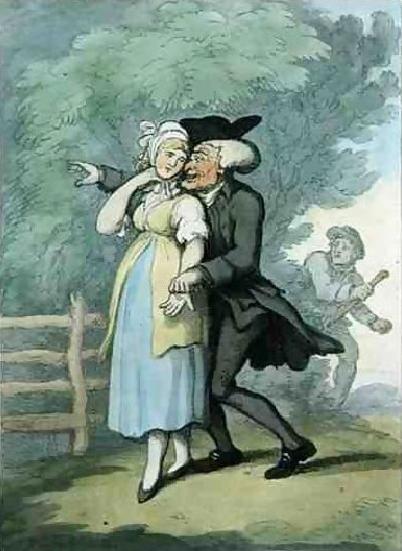

Diana Sperling's watercolor of a walk to a neighbor's house in mud

Diana Sperling painted her delightful watercolor sketches between 1812 and 1823. In two of the paintings, she shows precisely how difficult it was for ladies (and gents) to walk over poorly maintained roads – or no roads at all! One imagines that Jane Austen and her family, who were country gentry like the Sperlings, encountered similar difficulties when walking.

Charles Sperling conveys a lady over wet grass, by Diana Sperling.

In Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility, one can see Marianne in particular holding up her skirts and daintily traipsing over a London street as the party walks from their carriage to the Dashwood’s ball in London. I found this scene particularly interesting, for this is one of the few films that depict how difficult it was for ladies to keep their garments clean as they walked down London’s streets. Regency women must have collectively heaved a sigh of relief when hemlines became fashionably short.

Marianne Dashwood (Kate Winslet) holds up her skirt, shawl, and reticule as she walks gingerly towards the ball.

In Rolinda Sharples' Clifton Assembly Room (1817), one can see the lady on the lower right changing her slippers in the cloak room.

The problem of keeping one’s feet and skirts clean was solved by wearing pattens, although this practice was rapidly fading in the early 19th century.

Lady wearing pattens in snow. Image @City of London

In A Memoir of Jane Austen, her James Edward Austen Leigh wrote about his aunts Cassandra and Jane:

The other peculiarity was that when the roads were dirty the sisters took long walks in pattens. This defence against wet and dirt is now seldom seen. The few that remain are banished from good society and employed only in menial work…

As an illustration of the purposes which a patten was intended to serve, I add the following epigram written by Jane Austen’s uncle Mr Leigh Perrot, on reading in a newspaper of the marriage of Captain Foote to Miss Patten

Through the rough paths of life,

with a patten your guard,

May you safely and pleasantly jog,

May the knot never slip,

nor the ring press too hard,

Nor the Foot find the Patten a clog.

18th century fragment, iron shoe patten

A patten was an oval shoe iron that was riveted to a piece of wood and then strapped to the underside of a shoe. This unwieldy and loud contraption served to raise the shoe out of the mud or a dirty street. Even a clean street would sully the hems of delicate white muslin gowns, and thus ladies would commonly wear pattens. However, these contraptions were loud. As Jane Austen described in Persuasion:

“When Lady Russell, not long afterwards, was entering Bath on a wet afternoon, and driving through the long course of streets from the Old Bridge to Camden Place, amidst the dash of other carriages, the heavy rumble of carts and drays, the bawling of newsmen, muffin-men, and milk-men, and the ceaseless clink of pattens, she made no complaint..”

Early 19th century pattens

Pattens had been banned from churches for some time. As early as 1390, the Diocese of York forbade clergy from wearing pattens and clogs in both church and in processions, considering them to be indecorous: “contra honestatem ecclesiae”*. An 18th century notice in St Margaret Pattens, the Guild Church of the Worshipful Company of Pattenmakers, requested that ladies remove their pattens on entering; other English churches had similar signs, and in one case, provided a board with pegs for ladies to hang them on. One surmises that churches banned the use of pattens because of their loud clatter on stone floors.

Early 19th century pattens. Image @Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Constance Hill, who with her sister followed in the footsteps of Jane Austen a century after Jane’s death, described the noise of these raised iron clogs:

It is true that in bad weather ladies could walk for a short distance in pattens, which were foot-clogs supported upon an iron ring that raised the wearer a couple of inches from the ground. But these were clumsy contrivances. The rings made a clinking noise on any hard surface, and there is a notice in the vestibule of an old church in Bath, stating that “it is requested by the church-wardens that no persons walk in this church with pattens on.” – Constance Hill, Jane Austen: Her Homes and Her Friends

Pattens were clumsy platforms that raised the shoe a few inches from the ground. The most common patten after the 17th century was made from a flat metal ring which made contact with the ground. The ring was then attached to a metal plate nailed into the wooden sole. By the 18th and 19th centuries, men’s shoes had thicker soles and the wealthier gentlemen tended to wear riding boots, and thus pattens were worn only by women and working-class men in outdoor occupations. Soon, pattens were abandoned by ladies as well, and only the lower classes wore them as they went about their duties.

Pattens worn by a maid, 1773

There were three main types of pattens: one with a wooden ‘platform’ sole raised from the ground by either with wooden wedges or iron stands. The second variant had a flat wooden sole often hinged. The third type had a flat sole made from stacked layers of leather.*

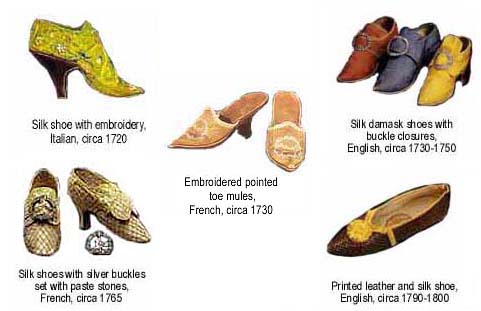

18th century silk shoes protected by pattens. Image @Wall Street Journal

One can imagine the sad state of paths and roads the world over, which necessitated the use of such clumsy footwear in England, America, Turkey, and China, to name a few countries.

Late 19th century Chinese porcelain patten shoes

Images of pattens over the centuries:

Read Full Post »