Inquiring Readers, Carolyn McDowall of The Culture Concept Circle has graciously allowed me to recreate Part One of her Two Part series. Find Part Two of Vanity Fair, but where is Mr Darcy? at this link.

Vanity and pride are different things, though the words are often used synonymously…pride relates more to our opinion of ourselves, vanity to what we would have others think of us” … Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, 1811

By the close of the eighteenth century archaeological investigations in Europe and Egypt were revealing more and more about the ‘antique’ past. The expansion of knowledge about antiquity revealed that ancient artists and writers had been accustomed to free expression in their work, with religion and honour paramount to any society’s daily existence. This revelation began changing the social and moral values and concerns of the many English, American and European societies who were all now ardently in search of truth.

Author Jane Austen lived in one of the most eventful, colourful and turbulent epochs in the history of England and Europe. The scenes of this extraordinary era were well recorded by many talented painters and sculptors of the day. In England this included the renowned painter Thomas Gainsborough.

In 1785, when Jane Austen was just 10 years old, he captured William Hallett and Elizabeth Stephen stepping out in style together for a morning walk. They were an elegant young couple, both 21 years of age and bound by their social status and the rules it imposed. They were due to be married in the summer of 1785.

They epitomize the stylish quality of the people who starred in Jane’s novels. He is discreetly dashing in a well fitting black velvet riding coat, an aspect of a gentleman’s costume that reflected his desire to be seen as ‘informal’, approachable, someone in touch with the political scene and social set of his day. He has the quiet confidence of a compleat gentleman.

She looks lovely in her softly floating silk dress, a smart black band accentuating her small waist and balancing perfectly with the simple black straw hat tied with a ribbon and feathers and placed at a jaunty modern angle on her very bouffant hair.

Strolling happily through a woodland landscape with an adoring dog at the lady’s heel they both appear full of hope in love and eagerly looking forward to a July wedding and a happy life together into the new millennium.

One of Jane Austen’s peers, renowned Scottish author of romantic novels Sir Walter Scott (1771 – 1832) said of Jane (1775-1817) that he believed the secret of her success was that she had chosen to write about ‘ordinary people doing things that happen in every day life’.Born at Steventon, Hampshire on 16th December 1775. The seventh child and second daughter of a scholar-clergyman and rector of the small country parishes of Steventon and Deane, Jane Austen’s family were members of the wealthy merchant class on her father’s side and aristocrats on her mother’s side. She was brought up in a country rectory and was, from contemporary descriptions, without pretension, her demeanour more ‘in a homely rather than grand manner’. Another way of saying that she was plain.

She and her family enjoyed amateur dramatics in the barn, playing charades, literary readings and musical evenings. While her older brothers hunted and shot game her mother industriously managed a small herd of cows, a dairy and, as a woman of sensibility and of some station in life, looked to the wellbeing of the local poor. Her father, as a rector, was regarded as a ‘gentleman’. He was an affable, courteous man welcomed by all the local landed gentry, and their well off tenants, as was her brother Edward, who just happened to be the heir to his cousin Mr. Thomas Knight’s estates. This meant Jane was able to move comfortably out and about in society and become a respectable observer in the luxurious world of the leisured classes.

It seems that her family more than likely fell into a category of middling people, a term coined by literary wit and social commentator Horace Walpole on his return from the continent in 1741 “I have before discovered that there was nowhere but in England the distinction of being middling people. I perceive now that there is peculiar to us middling houses; how snug they are” The country gentry actively supported the ruling and upper classes by cultivating an ambience of politeness, a keen, though delicate sensibility, which was always balanced by displaying a great deal of practical common sense.

Their gentrification was reflected in how they dressed, dined, performed and were entertained, in a selection of social settings. They rotated from the socially competitive atmosphere of London’s elegant drawing rooms to the cheerful gaiety of Bath’s assembly’s room and they also enjoyed the more robust attractions of popular coastal resorts like Brighton, which were after 1792 was also frequented by the Prince Regent and his entourage.

They strove for aesthetic perfection urged on by their awareness of the ‘antique’, while striving to emulate the ideal – classical perfection, The classical ideal had flowed over into the landscape during the eighteenth century and small temples originally designed as refuges from the hot Mediterranean sun, became focal points of beauty.

At the time of Jane’s birth Horace Walpole, for whom literacy mattered, was using decorative ornament inspired by a literary and pictorial interest in Gothic architecture at his house Strawberry Hill.

He and his peers benchmarked standards for excellence in taste and style well recognised by Jane and the burgeoning middle classes, who wished to emulate them.

Horry took what he liked and used it the way he wanted and his character seemingly enjoyed total satisfaction by ‘imprinting the gloomth of abbeys and cathedrals on one’s house.’

Jane’s brother Edward Austen Knight eventually inherited the very gentrified Godmersham Park in Kent and two of her other brother’s Francis and Charles had distinguished careers in the British navy. Francis received a knighthood and the much coveted order of Bath and Jane’s brother Charles bought topaz crosses for his two sisters, going without to purchase them.

In the Christian understanding perfect love makes no demands and seeks nothing for itself, and this was the quality of the people that abounded in so many of the characters in Jane Austen’s life and in her novels. Jane enjoyed what she herself called ‘life a la Godmersham”.

Her brothers hunted in Edward’s park, played billiards and entertained in a style that amused Jane. Writing from Godmersham in 1813 she commented “at this present time I have five tables, eight and twenty chairs and two fires all to myself”.

The Royal navy were winning great victories on the continent at the time. For the leisured classes in Jane’s novels the war was something that happened in the newspapers or far out at sea. Although her brothers were involved, many of these events seemed very remote and Jane and her peers continued to pursue their daily activities such as music, painting, playing games and writing with great enthusiasm comforted in the knowledge that England had the best navy in the world.

The Duke of Wellington’s victories and Admiral Nelson’s death at the Battle of Trafalgar caused a nation to mourn as well as celebrate wildly for twenty years afterward. And all manner of goods were named for him including “Trafalgar chairs”, which along with the sofa table were two very popular pieces of furniture during the Regency period.

Country houses and their beautiful parks were not simply the expressions of a wealthy ruling class for Jane and her contemporaries. They represented an ideal civilization with a mixture of self-esteem, national pride and uncompromising good taste. For the rest of the population they reflected the unequal structure of a society where a third of the nation’s population faced a daily struggle to survive. From the monarch to the poorest of the land there was a pyramid of patronage and property. At the base of which in 1803 a third were the labouring poor, the cottagers, the seamen, the soldiers, the paupers and the vagrants who lived at subsistence level.

Jane’s letter to her sister Cassandra in 1799 highlights the point, when a horse her brother purchased cost sixty guineas and the boy hired to look after him four pounds a year. Those employed in service counted they lucky, but even in well off household’s service conditions were still fairly primitive. Jane said “Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery. I quit such odious subjects as soon as I can”. The contrast of the battlefield and the ballroom are apt as a reminder of the powerfully opposed elements that made up the England into which Jane was born and in which she grew to maturity.

George, Prince of Wales, the future George IV was the very active, central focus of the style we now know as the Regency period. His personality was complex and he often indulged in fantastic flights of fantasy.

As a young man he had fair hair, blue eyes and pink and white complexion, and a tendency to corpulence. As he grew to maturity he gained considerably in popularity due to his good looks, high spirits and agreeable manners.

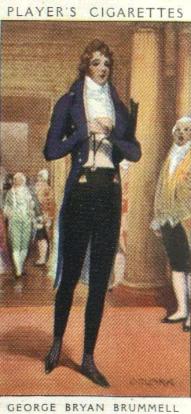

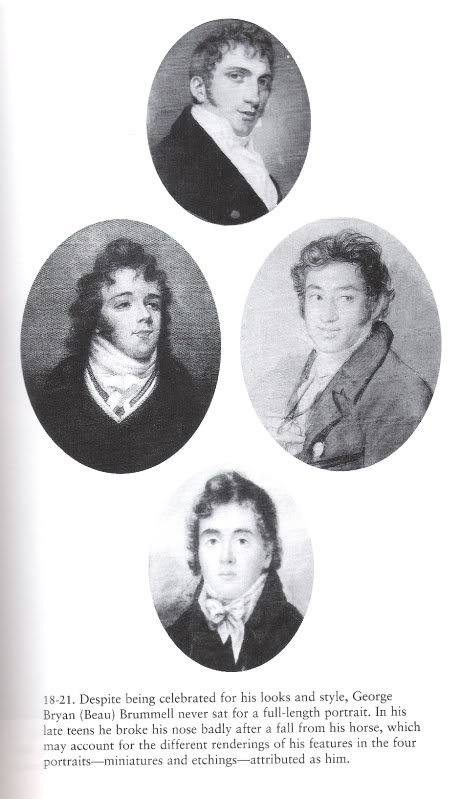

He was the darling of the fashionable world. George Bryan Brummell (England, 1778-1840) became the most famous of all the dashing young men of the Regency. He was not of aristocratic birth, but the son of the secretary to Lord North.(George III’s Prime Minister who played a major role in the American Revolution). Educated at Eton, the Beau became known as Buck and was extremely well liked by the other boys. He spent a short period at Oriel College, which has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford, dating from 1324.

The Prince Regent was told that Brummell was a witty fellow, so he obtained an appointment for him in his regiment (1794). Brummell became a Captain of the Tenth Hussars and was constantly in the Prince’s company.

In the circles around the Prince he was known as a virtual oracle on matters related to dress and etiquette. As the new dictator of taste he established a code of costume.

A typical Regency outfit for day wear was a jacket cut away in front and with tails at the back. There was no waist seam, a feature present in Victorian coats. The open area around the hip had a distinctive curve pulling slightly around the waist.

Even more notably, the sleeves were particularly long and seated high on the shoulder. There are virtually no shoulder pads. Normally jackets had fabric-covered buttons. An exception was blue jackets with brass metal buttons–an association with military styles.

At night it was all sartorial splendour, rich textiles velvet, brocades, silks, all combined with a great deal of elegance, the costume for a gentlemen including a black coat.

Today we would say the Beau was very well connected, an important part of an influential network and a man to know.

It was in 1784 when the Prince of Wales took one look at Maria Fitzherbert standing on the steps of the Opera and fell instantly in love with her. He was totally besotted and would only attend parties and events if the hostess assured him Maria would be both there – and sat next to him!

Following a dedicated and unsuccessful pursuit of Mrs. Fitzherbert, Maria was surprised one evening by a visit from some of the Prince’s men. They had found him weak and bleeding in his home Carlton House, whose interiors were among the wonders of the age.

They told her the Prince had tried to commit suicide and Mrs. Fitzherbert, accompanied by the Duchess of Devonshire, rushed to his side whereupon he persuaded Maria to marry him. In 1785 George, Prince of Wales Prince married Mrs. Fitzherbert (1756 –1837) a Roman Catholic who had been married twice before. The couple was happy and while society seemingly accepted the unconventional pair the marriage rocked court circles, which could not cope with the thought that a Prince might marry a divorced woman.

Eventually the Prince would be forced to put her aside and it did not help his cause that his friend Beau Brummell, to whom Maria took a pronounced dislike, disapproved of the liaison.

Initially the Prince spent a great deal of time and effort building Maria his bride a house nearby his home Carlton House in Pall Mall and decorating his own home. He ran up such huge debts the only way his father, the King would agree to help him out and pay them was if he put aside Maria and marry Caroline of Brunswick, for political reasons, which he did.

In 1793 George, Prince of Wales visited the seaside town of Brighton, and ordered the subsequent renovation of a small house he purchased from one of his footman. Architect, Henry Holland, well known for his refined Francophile tastes, fashioned it into a splendid marine villa with gentle curving bays, wrought iron balconies and long sash windows, and it was much admired and set a standard for marine villas for many years to come. Mrs. Fitzherbert and the Prince parted company upon the marriage to Princess Caroline, however following the birth of his daughter; the Prince recommenced his pursuit of Maria.

Maria was wary, however and upon asking the Pope for guidance she was informed that she was the only true wife of the Prince so she returned to him. Again the couple spent a lot of time entertaining at Brighton and London.

Bathing in the sea had become very popular, with the Prince’s own physician recommending he bathe daily and bathing machines were set up especially for that purpose. All over Brighton, rows of small villas were built, echoing the Pavilion’s shape.

Some of the newly popular ‘seaside’ villas in Brighton were glazed with a smart material called ‘mathematical tiles’ which enabled villa houses to be built of less expensive brick and then ‘faced’. Introduced into the English architectural system after 1700 in England they were hung on buildings originally built of timber to give the appearance of higher quality brick walls. Today they are still not easy to recognise and are often mistaken for conventional brickwork. Black, glazed mathematical tiles are easy to discern, however, and may be seen at many locations in Brighton.

Painted furniture and at wall decoration ‘Etruscan style’ at Osterley House. The interiors were designed by Scottish Architect Robert Adam

Interior arrangements whose design focus was based on classical order reached the height of its popularity through the neoclassical style of Scottish architect Robert Adam between 1760 and 1793. The expansion of the neo-classical style was fuelled in the last half of the eighteenth century because of the interests of English Grand Tourists in the new discoveries being made at Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy.

Not only the shapes of the furniture were greatly influenced – for instance in the use of animal forms as supports for tables and chairs – but also the colour and decoration used for painted furniture, which was to be found in grand houses as well as much simpler gentry houses. Much of the charm of collecting such pieces lies in the rather primitive way the decoration was thought out and executed and many examples of very sophisticated simulated bamboo pieces were destined for important rooms.

Adam’s interiors could have easily been the inspiration for those of the formidable Lady Catherine de Burgh. Her country house Rosings in Pride and Prejudice was described by Jane as an interior of ‘fine proportion and finished ornaments’

Vanity fair, but where is Mr Darcy? – Part 2

Carolyn McDowall, April 2011 ©The Culture Concept Circle

A recent post on this blog mentioned the film,

A recent post on this blog mentioned the film,

Horse Collar Tie

Horse Collar Tie

THE Cravate Americaine is extremely pretty and easily formed, provided the handkerchief is well starched. When it is correctly formed it presents the appearance of a column destined to support a Corinthian capital. This style has many admirers here, and also among our friends the fashionables of the New World, who pride themselves on its name which they call Independence; this title may to a certain point be disputed, as the neck is fixed in a kind of vice which entirely prohibits any very free movements –

THE Cravate Americaine is extremely pretty and easily formed, provided the handkerchief is well starched. When it is correctly formed it presents the appearance of a column destined to support a Corinthian capital. This style has many admirers here, and also among our friends the fashionables of the New World, who pride themselves on its name which they call Independence; this title may to a certain point be disputed, as the neck is fixed in a kind of vice which entirely prohibits any very free movements –